While high-quality, age-friendly, affordable housing will be a critical need for all of America’s growing number of aging households, for two reasons, the needs of older single women require particular attention for policymakers, providers, and others.

First, because women generally outlive their male spouses or partners, they will continue to be a major share of all older households. Women living alone already comprise 44 percent of all households (and three-quarters of all single-person households) where the householder is age 80 or over (

Figure 1). Such women—particularly women who rent rather than own their homes—are among those older people who are most at risk of housing, financial, and health insecurity as they age.

Source: JCHS tabulations of 2014 American Community Survey data.

These challenges are one aspect of a larger demographic transformation that will occur over the next several decades as the aging of the baby boomer generation and increases in longevity swell the elderly American population. The US Census Bureau projects that the population aged 65 and over will reach 79 million by 2035, an increase of more than 30 million in just two decades (

Figure 2). Further, longer life expectancy could nearly double the number of individuals aged 85 and over to 12 million by 2035.

Source: US Census Bureau 2015 Population Estimates and 2014 National Population Projections.

This so-called “Silver Tsunami” has already begun to reshape housing needs across the nation, generating demand for accessible, affordable housing that can help older households age safely and comfortably in place. As people age, finding the resources to make age-friendly home modifications, to pay for assistance with daily activities and self-care, or even keep up with housing payments often becomes increasingly difficult. The risk of falling into financial and housing insecurity grows when households cross into their retirement years (age 65), as incomes begin to drop dramatically while out-of-pocket health care expenditures rise (

Figure 3). While some households may be able to adequately supplement shrinking incomes with retirement savings, home equity, and other forms of wealth, a

recent report from the Employee Benefit Research Institute shows that many households on the verge of retirement today have insufficient savings to independently finance their retirement years.

Source: Median household income derived from JCHS analysis of 2014 American Community Survey Data. Out-of-pocket personal health care spending data derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ National Health Expenditure Data, 2012 Age and Gender Tables.

Some aging households are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of financial insecurity and loss of independence. Older individuals who live by themselves, for example, often have neither the option to seek help with daily activities or unexpected emergencies from another person in the home, nor the financial cushion of a second income from a spouse or housemate. Women are disproportionately impacted. Older women, who are more likely to live alone in later life, continue to have lower lifetime earnings than their male peers, and are also more likely than men to need

expensive long-term care. As a result, single women are projected to experience the largest retirement savings shortfalls over the next several decades.

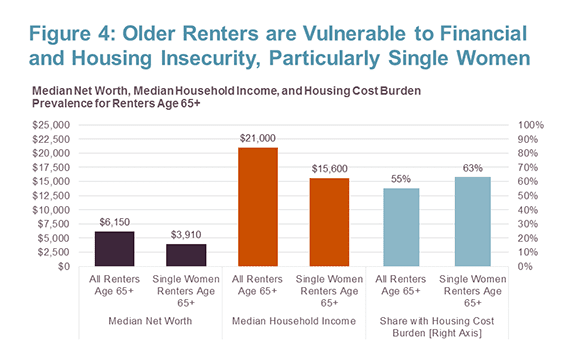

Single older women who rent rather than own their homes are most at risk of falling into housing and financial insecurity. Older renters lack housing equity and typically also have far lower overall net worth than older owners, leaving many unable to sufficiently bolster limited retirement incomes with financial reserves. Analysis of the most recent Survey of Consumer Finances data shows median net worth for renters age 65 and over to be just $6,150—a mere 2.4 percent of median net worth for owners of the same age. For single older women renters, median net worth is even lower—just $3,910—and the risk of financial insecurity is especially high, intensified by comparatively lower incomes and even higher housing cost burdens than older renters overall (

Figure 4). In 2014, annual median income for single women renters age 65+ was just $15,600. Meanwhile, fully 63 percent had a housing cost burden, with 38 percent paying at least 50 percent of their income toward housing. This combination of high housing cost burdens, low incomes, and little net wealth mean that older single women renters have few resources left to pay for assistance with self-care and other needs. But with

median annual costs for non-residential long-term care ranging from $17,680 for adult day health care to $45,760 for full-time homemaker services, formal care is far out of reach for many single older women. With the aging of the baby boomer generation poised to increase the number of single older women living alone to unprecedented proportions over the next several decades, finding ways to mitigate housing and financial instability among this most vulnerable group is fast becoming a critical need.

Source: JCHS tabulations of 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) and 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) data. Dollars are nominal.

Notes: "Moderate" burden is defined as housing costs of 30-50 percent of income. "Severe" burden is defined as housing costs of more than 50 percent of income. Due to survey design differences between SCF and ACS, "single women renters" refers to single-person female-headed households for data describing median household income and housing cost burdens, and to women whose marital status is "single" for data describing median net worth.

As

previous Joint Center work has highlighted, our aging population will re-shape housing demand across the nation over the next several decades, greatly increasing the need for affordable, accessible, age-friendly housing. Ensuring that older single women, especially renters, have access to high-quality housing and home care will require particular attention, given their low incomes, low wealth, high likelihood of need for care, and the absence of a spouse, partner, or other household member able to provide daily assistance in the home. As the older population grows in coming years, it will be critical for policymakers and providers to take special care to ensure that our nation’s most vulnerable older households—particularly older single women—have access to tools that can help them age safely and successfully in their own homes and communities. Such tools may include affordable rental options and in-home care and homemaking services, as well as loan and grant assistance opportunities for age-friendly home modifications. Finding ways to expand access to these and other solutions will be critical to protecting the health, happiness, and well-being of our aging population today and in years to come.